Opinion: Importing sunshine: a fairer power plan for New Zealand

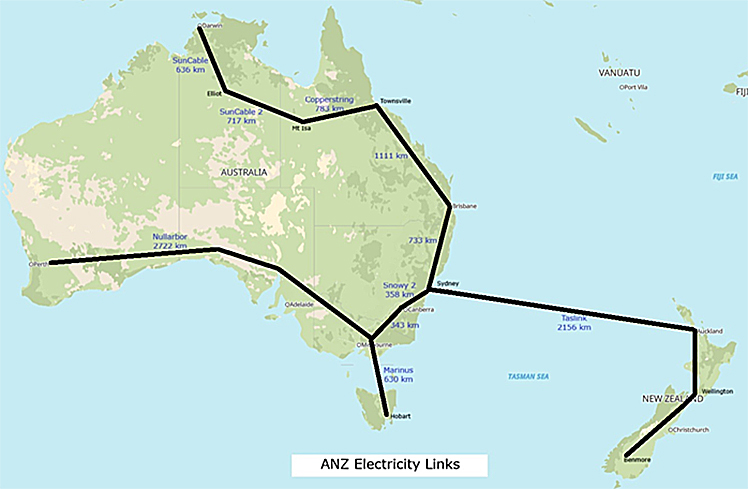

Fig.1: ANZ Electricity Links concept – the time-zone "sunshine spine".

.

■ Most of us don’t follow Government electricity policy. We just want power that is reliable, affordable and clean, says Graeme Weston.

The good news is there’s a simple, practical idea that ticks all three boxes: use a smart undersea cable to move cheap sunshine across time zones and let our cars act like small batteries.

Do those two things and we can ease the dinner-time price spikes, reduce dry-year risk, and bring bills down – without dipping into taxpayers’ pockets.

The proposal has a New Zealand pedigree.

Far North Solar founders Graham Homewood and John Telfer call their concept Taslink: a high-capacity HVDC cable landing near Auckland and connecting to the Australian grid near Sydney.

Because Perth is five hours behind us, it’s 2pm solar abundance is at our 6pm demand peak.

Every sunny afternoon over there can become cheaper energy for our dinnertime over here. Taslink also works in reverse each morning: when our solar and wind are producing and Australia is ramping up, we sell west. That creates a daily revenue stream for Taslink.

Across the Tasman, HyEnergy and partners are pursuing a West-to-East HVDC concept across the Nullarbor Plain, so the very sunny west can ship power into South Australia and Victoria. The same solar arbitrage formula. Join these routes up and you get an Australasian “sunshine spine”: Perth g South Australia/Victoria g Sydney g Auckland. Now add two force-multipliers.

First, curtailment – Australia already switches off gigawatts of solar and wind in the middle of the day because there’s more supply than local grids can absorb. Second, Vehicle to Grid (V2G) – two-way charging that lets electric vehicles (EVs) charge cheaply at lunch and sell a little back into the evening peak. Curtailment becomes our fuel; EVs become the flexible engine.

How much spare energy are we talking about? Analysts have recorded 10 GW of daytime renewable curtailment across the Australian Network on bright days. New Zealand would seldom need more than about 4GW at once to transform the winter 6pm peak and save water in the lakes.

In other words, we can buy only what we need, when we need it, at the lowest price of the day – because otherwise that energy is being spilled by the Australians.

The impact at home is immediate: cheaper imports at peak times push prices down, and by leaning on Aussie sun we preserve South Island hydro for the truly dry weeks.

EVs multiply the benefit. The latest New Zealand study on Vehicle-to-Grid finds a typical commuter EV can deliver around $2000 a year for owners by charging off-peak and exporting a small slice at the peak.

Picture tens of thousands of cars plugged in at home or work: they fill on low-cost lunchtime power and, if the price is right, discharge for an hour or two in the evening without dropping below the owner’s chosen battery floor. That trims the very hours that make electricity expensive, reduces the need for gas peakers, and gives households a new income stream that helps pay off the vehicle and the charger. None of that requires a new levy – just fair network pricing that pays homes the same peak rate for export that they are charged for import.

Taslink is also a cleaner, busier dry-year hedge. If lakes are low, we still have access to Australian solar and wind and to Tasmanian hydro via Australia’s own interconnectors. Compare that with building a giant seasonal battery like Lake Onslow at about $16 billion.

Onslow would mostly sit idle by design – perhaps 80 percent of the time – and only earn when we are already in trouble. Taslink is the same order of cost but would earn every sunny day and every winter evening by arbitraging time zones and soaking up curtailment.

The 100,000-plus EVs needed for reliable daily load-shifting are bought by their owners, not by the Crown. Meanwhile, as we electrify transport, we displace imported petrol and diesel – billions of dollars a year – and keep that money circulating in the local economy. Energy security improves because we’re harvesting homegrown sunshine, not burning foreign fossil fuel.

Crucially, this is not a plea for subsidies. It’s a plea for good rules. We need symmetrical peak-export payments at the local level, so households and small businesses get paid fairly to help.

Distributors (poles and wires companies) should be rewarded for utilisation – keeping their assets full and useful – rather than simply for building more hardware.

And interconnectors like Taslink should be open-access, with a transparent cents-per-kWh-per-kilometre toll and published loss factors so competition, not incumbency, keeps costs honest.

That’s the spirit behind Dynamic Locational Marginal Pricing (DLMP, locational prices that reflect real delivery costs) rather than the blunt “build and earn a return” incentives (the current regulated model) that push bills up.

Some will ask: if this is so obvious, why isn’t it happening already? One reason is policy distraction. The Government commissioned the Frontier Economics review to examine competition and dry-year risk.

Rather than backing flexible, contestable firming, ministers are moving to procure a small LNG import terminal – much like the years spent studying Onslow.

The risk is the same: once gas becomes the centrepiece, private investors in wind, solar and storage sit on their hands because the generation they would produce to recover costs would be directed to a fuel ship. That delays the building of cheaper renewables, prolongs high prices, and keeps dividends flowing from scarcity rather than service. New Zealand industry and households will pay high prices for the 10-year detour.

There’s a better sequence. Build excess renewables fast; make room for them with batteries and fair peak-export payments; and let a private-finance interconnector turn wasted Aussie sunshine into our evening supply.

The day-to-day economics are straightforward. When the Sydney price, Taslink distance losses and toll is lower than the Auckland price, the cable imports and the price collapses.

When we have spare wind or hydro in the morning and prices are higher across the Tasman, the cable exports and earns. We can afford to overbuild more solar and wind as a fuel backstop, hydro does what it is best at – seasonal storage – because we’re no longer consuming precious water just to cover the dinner ramp. Any excess renewables generated in wet years due to overbuild, we can export to Australia.

For consumers, the result is simple. Daytime bills fall as more load shifts into the cheap window. Evening spikes disappear because imports, batteries and EVs compete with hydro to set the price. In a dry year, we import clean energy from Australia instead of firing up coal or paying through the nose for scarce gas.

EV owners see new credits on their bills for helping at the peak. And because the system is used more of the time, the per-kWh delivery cost of the wires falls as fixed costs are spread across more energy.

For investors, Taslink and the sunshine spine look like an efficiency play with daily cash flows: curtailment capture, east-west arbitrage and dry-year hedging.

For policymakers, it’s a way to lower bills and improve security without government funding. All it takes is a handful of targeted decisions: symmetrical export pricing, open-access rules, and fast-tracked approvals for the cable corridors and for the wind and solar that will run on them.

New Zealand does not have to choose between reliability and affordability. We can have both by moving energy to where it’s worth the most, when it’s worth the most – every day.

That’s what Taslink and V2G make possible. It’s time to stop paying top dollar for imported fuel and start harvesting sunshine instead.