Mayor's talk: What does affordable mean?

.

A language works only if everyone has a common understanding or definition of the words we use. And yet the word “affordability” is bandied about all the time in council, especially in regard to rates, and I am not sure we have that common understanding.

The dictionary defines affordability as “able to be afforded: having a cost that is not too high”. But what is too high?

For someone like Elon Musk, who is worth about $US355 billion, virtually anything is affordable.

For me, on the other hand, many things are unaffordable, although I guess I am reasonably well-off compared to some. Nevertheless, sticking my hands in my pocket hurts a bit.

When it comes to the setting of rates, myself and each of the 10 councillors I share the table with have a different view of what is affordable to the average resident of our district.

The financial situation of each councilor is different, and we circulate in different spheres and hear different things. It is to be expected, therefore, that each of us has a different and subjective notion of what affordable means to the people around us.

For more than three years now, I have been trying to have a serious objective discussion about what affordable means in the context of the people who live in the district I was elected to represent.

By this, I mean that I want an objective and quantitative measure of what affordable means and a robust methodology for getting to that number.

Logically, the discussion over affordability should precede the development of an annual or long-term plan where priorities and budgets are set.

I just can’t see how it is possible to set rates and decide how money is spent if we don’t have an idea of what affordable means to the ratepayer?

It has been argued by some in my council that since 97 percent of residents pay their rates, then the rates are by definition affordable to most.

Although this sounds reasonable, we all know that it isn’t that simple. You might call it a logical fallacy.

One reason that the ability of council to collect rates off ratepayers may not be a good measure of affordability might be that since there is legal obligation to pay, folk are forced to make sacrifices.

Paying Whakatāne District Council rates may mean a person or household has to forgo other, often essential, goods and services.

I have tried to start the discussion about affordability using the income that folk actually have available to run their households. That number is the median household income in our district. But what is a median household income?

We all know that different households have different income levels and therefore there exists an income distribution across the district.

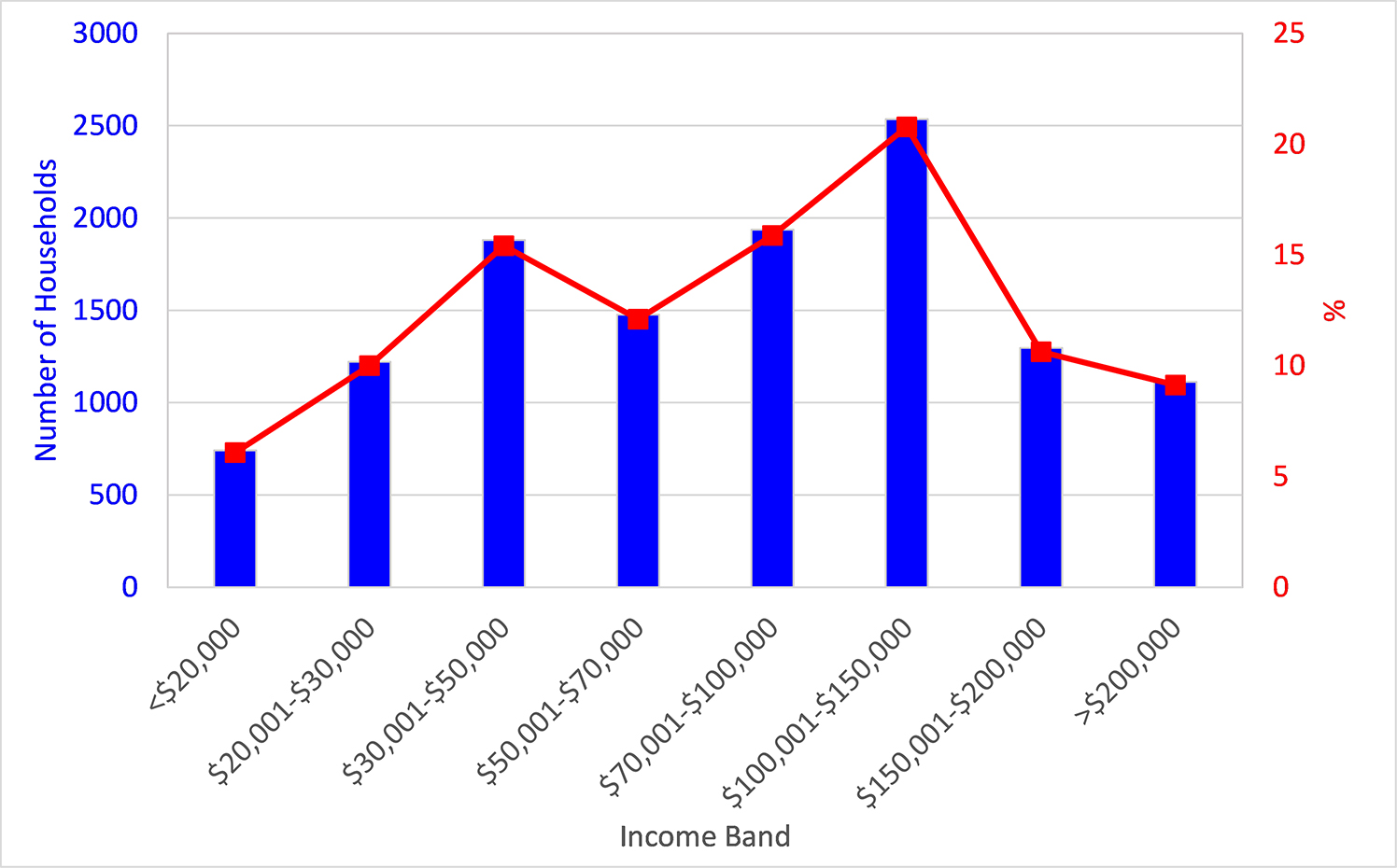

The graph of income distribution is pictured above, and I put it together from 2023 census data.

The different blue bars represent the numbers of households on the vertical axis (blue) with income in the range on the horizontal axis. The graph shows that about 2535 households (21 percent) have annual pre-tax incomes in the range $100-$150,000. This is quite a broad range of $50,000, but it is the only data available at the moment.

It is also evident that quite a large proportion of the district has incomes much lower than this while only 1113 households (9 percent) have incomes exceeding $200K.

The median is the central tendency or the middle of the salary distribution and in 2023 it was about $83,000 in our district. That means that half the households have higher incomes than $83,000 and half have lower.

To my way of thinking, since the income distribution is reasonably well known, the median is a reasonable starting point for any discussion of affordability.

The raw data is available from sites such as Stats NZ and Infometrics.

Although it is all very well to know these income levels, the important thing is what you can actually purchase by way of goods and services after income tax has been deducted.

Deducting income tax from a gross annual household income of $83,000 would leave about $5367 per month. Payment of a mortgage or rent from that would take a big chunk of what is left over.

Let’s consider the case of a three-person family on the median income with an average 20-year mortgage at current interest rates.

That family would spend about 45 percent of its income on servicing the mortgage.

In other words, after paying tax that median income family would be left with about $2952 to live on per month. Some families, of course, have lower mortgages and some higher mortgages. It can be estimated that about 33 percent of the district pays rent.

I have calculated how much a family on the median income paying off the average mortgage having this monthly net income ($2952) would have to pay toward fixed expenses such as rates, insurance, power, water and so on and then I have subtracted the costs for food, fuel, clothing and other consumer goods.

When all this is said and done, I figure that there is not a hell of a lot left over. Rather, unless this household was very disciplined and stuck to the bare necessities of life they would struggle to get to the end of the month on the available income.

It is extremely important and worth repeating that I have done the numbers based on the median income, which is the middle income.

That means that half of the families in the district have lower incomes, and many have much lower incomes. These households are more likely to be those paying mortgages or rents.

The numbers I get are not ridiculous as they are supported by my own experiences.

When I lived in Australia in about 2007 my net household income was about $5200 per month. My single income family comprised a wife and two toddlers and we received $400 per month family benefit from the Australian Government, and I had a $250K mortgage.

By virtue of living in an outer southern Sydney suburb, I had to run two cars although fuel costs were only about 70 cents per litre at the time.

My annual council rates were about $1200 per annum. While on the face of it my circumstances did not seem too bad, I was only just making it to the end of the month.

Today, for the household on the median net household monthly income of around $5367 living in our district that is paying rent or a mortgage things are tight.

Then there is the case of people living off national superannuation, of which about 20-30 percent are either still paying off a mortgage or paying rent.

For superannuitants in this category, things are particularly difficult.

Although rates rebates are available to folk with low incomes, life is still pretty tough.

Since rates rebates are assessed on income, you can still have money in the bank and receive a rebate as long as you don’t earn too much interest.

Council also has remissions and postponement policies which I urge these folk to explore.

Of course, those with plenty of money will always be able to pay whatever rates council wants to charge.

They may not want to pay, but they have the capacity.

There are even those who espouse that they are happy to pay rates to provide services for future generations.

A few years ago, I went through all of these numbers for a family in our district on the median household income paying rent and I couldn’t make a budget work without leaving out a lot of stuff that would not be considered luxuries.

For instance, that family would find it very difficult to repair a car, buy a replacement fridge and pay for school uniforms, an unexpected dental or medical bill and so on.

For a family with less than the median household income things would be much worse.

Talking about the median income is all very well. However, every household has specific circumstances and so the only way of deducing what a particular household’s level of affordability is involves using the household income and making all the appropriate deductions to determine what is left over at the end of the month.

The objective of this column has been to engender discussion over a more objective and rigorous method of determining affordability.

To take affordability beyond a stab in the dark. The task is not a simple one and what I have suggested is by no means perfect.

It could however, be a starting point because affordability surely has to do with the income that people have and for that we do have numbers.